BLOG & ARTICLES

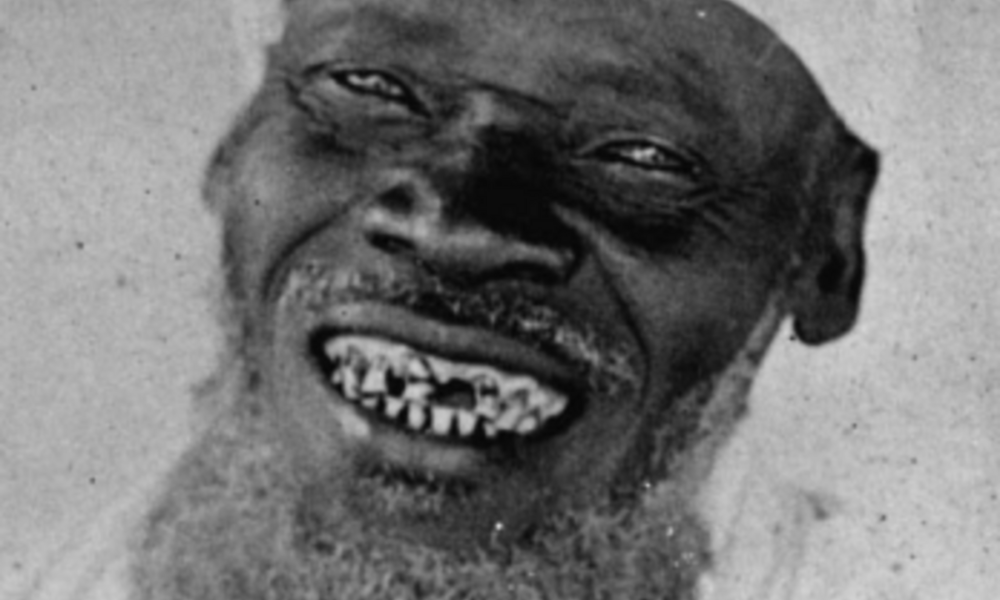

Unveiling the Legacy of Sidi Mubarak Bombay: A Remarkable African Explorer in 19th Century British Expeditions

His exceptional competence and vital role in high-profile expeditions earned him a Silver Medal from the Royal Geographic Society in 1876 in recognition of his contributions to British exploration efforts in Africa.

Sidi Mubarak Bombay was among the most extensively travelled sub-Saharan Africans in the nineteenth century. He was ultimately honoured for his assistance and contributions to British explorers and adventurers. Bombay, of the WaYao tribe, was born in the Ruvuma region of southern Tanzania around 1820. Separated from his parents at the tender age of 12 and taken to captivity by Arab slavers, he eventually ended up in Gujarat in India, where he spent two decades as a slave. He gained his freedom following the death of his owner and returned to his motherland.

Safely back home, he enlisted in the Sultan of Zanzibar’s army, where he met British explorer John Hanning Speke, who hired him as a guide for an initial expedition led by fellow Briton Sir Richard Francis Burton to locate the source of the Nile. Bombay was serving as one of Speke’s two caravan captains when, in 1858, Speke became the first European to reach (“discover” In British terms—never mind that it had been there the whole time, and the local inhabitants had exploited and revered it since the dawn of time itself—and had been ‘pre-discovered’ by Arab slave traders some 700 years erstwhile) Lake Victoria.

INTERMISSION: Now this curious misnomer came about when the hitherto obscure Speke shot to quick fame by “discovering” it as the source of the Nile. Upon seeing this vast expanse of water, Speke could scantly hold back his emotions and, without reference to anyone, named it for his contemporary monarch, Queen Victoria.

He then proceeded to eulogise his adventures in a speech to the Royal Geographic Society while his partner-in-expedition, a sickly Richard Burton, lay invalid in the Dark Continent. Understandably, Burton was outraged. He insisted that Speke’s discovery, made during his convalescence, was an enormous pile of freshly laid dung; whereupon, to preserve honour, the two gentlemen pencilled in a duel before the Society. The dispute was finally and fatally settled when Speke, mysteriously and quite inexplicably, expired of a self-inflicted gunshot wound a day prior to the contest.

A film released in 1990 revealed a completely new and wholly unexpected insight into the Speke-Burton affair if you’ll excuse the pun. ‘Mountains of the Moon’ (excuse another pun!) hints at a sexual relationship between the two distinguished gentlemen explorers, and goes ahead to outrightly portray Speke as a closeted homosexual, and his partner a rampant heterosexual male. Go figure.

Their remarkable fallout notwithstanding, Burton and Speke did share some good times. On his maiden voyage, for instance, Speke joined the then already-famous Burton on an expedition to the coast of Somalia. Unfortunately, and not unlike their American imitators one and a quarter centuries or so later, they found Somalia a hard nut to crack even at the best of times, Blackhawks down or otherwise. Anyway, the meticulously planned odyssey was not to be and came spectacularly a cropper almost the moment they hit the shore. Their party was instantly ambushed: Speke was captured and repeatedly stabbed with spears, before somehow emancipating himself and fleeing; the more experienced Burton managed an altogether clean getaway, save for a javelin impaling both his cheeks.

When not exploring the geography of faraway territories and/or his companion’s, Speke kept busy as an infernal racist. A prolific writer, he is also famous for propounding the apocryphal Hamitic Hypothesis in 1863, in which he postulated that the Tutsi were descended from the Biblical Ham because they had “lighter skin tones and more European features” than the Hutu over whom they lorded. No need to revisit here how this came to a head in 1994.

Initially, Speke and Bombay communicated only in Hindi, but Bombay eventually added English, Arabic, and Kiswahili to his lexicon. He reconnected with Speke in 1860 when he, alongside Scottish explorer James Augustus Grant, discovered that Lake Victoria eventually connected with the Nile. His British employers renamed him Mubarak, but he continued to use Bombay, the name of his youth, that he had adopted in India. He gained a reputation for diplomacy when dealing with tribal chiefs, as well as managing caravan logistics and administering the African labourers under his care.

However, his service with journalist-turned-explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who tracked down missionary David Livingstone in November 1871, was fraught with challenges unrelated to exploration. Like Speke, Stanley needed Bombay’s help in tracking down the source of the Nile—later determined to be tributaries that flow into Lake Victoria—and to locate the “missing” Livingstone. Despite his obvious value to Stanley, the explorer admitted in his memoirs that he regularly insulted and beat the reedy and diminutive Bombay, particularly when he suspected insubordination from the often-outspoken African.

INTERMISSION THE SECOND: Talking of Stanley’s journals, among his more famous exploits, was his search for Dr. David Livingstone and the immortal words he uttered upon finding him: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” However, aspersions have been cast upon the authenticity of this celebrated salutation and is likely a fabrication. Stanley tore out of his diary the pages relating to the encounter and Livingstone’s account fails to summon these words.

In 1875 Verney Lovett Cameron hired Bombay as a guide when he became the first European to cross equatorial Africa from coast to coast, from Zanzibar to Angola. This was Bombay’s final major expedition into the African interior.

It has been estimated that, as the unsung explorer, Bombay tallied in excess of 9,600 land miles through the interior of Africa, and sailed far more nautical miles in the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the waters along coastal Africa. His exceptional competence and vital role in these high-profile expeditions earned him a Silver Medal from the Royal Geographic Society in 1876 in recognition of his contributions to British exploration efforts in Africa, and in particular, the search for the source of the Nile. The Society also granted him a lifetime pension. In his twilight years, Bombay worked for the Church Missionary Society, helping missionaries spread the gospel across the African continent. Sidi Mubarak Bombay died in Tanzania on 12 August 1885 aged 65.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.